Reflection X: Typology in Genesis 22 and Exodus 24

Introduction

The narratives of Abraham’s near sacrifice of Isaac in Genesis 22 and Moses’ ascent to Mount Horeb in Exodus 24 stand as two defining moments in salvation history. Both passages engage in a dynamic interplay between divine command and human response, foregrounding the role of faith, obedience, and covenantal fidelity. At the core of these sacred narratives abides a theological vision that transcends their immediate historical milieu. In truth, they serve as historical icons—windows through which the faithful behold Christ Himself. As the Lord testifies in the Gospel according to Luke, everything written in the Law of Moses, the Prophets, and the Psalms concerns Him,[1] thereby disclosing that these ancient accounts find their ultimate fulfillment and meaning in the incarnate Logos.

Typological Similarities Between Genesis 22 and Exodus 24

Genesis 22 and Exodus 24 reveals remarkable thematic similarities, particularly serving as icons to the sacrifice of Christ and the role of the mountain as a place of encounter with God. In both accounts, the mountain serves as a sacred space where the divine and human spheres intersect. Abraham ascends Mount Moriah in obedience to God's command, fully prepared to offer his beloved son. Similarly, Moses ascends Mount Horeb in response to God's call, entering direct communion with the divine presence.

The mountain, in Orthodox theology, often symbolizes the ascent of the soul towards God, a theme that finds its fullest expression in the Hesychastic tradition. St. Gregory Palamas frequently employs the biblical image of Christ’s Transfiguration on Mount Tabor as a parallel between the physical ascent of the apostles onto the mountain and the spiritual ascent undertaken through ascetic labor. For St. Gregory, the purification of the heart through ascetic practice is the indispensable “path” that allows the Christian to stand, so to speak, on the spiritual summit and receive the vision of the divine light.[2] Just as Abraham was prepared to give up his son, and Moses was willing to enter the presence of God, so too must the Christian surrender personal will in order to attain divine union.[3]

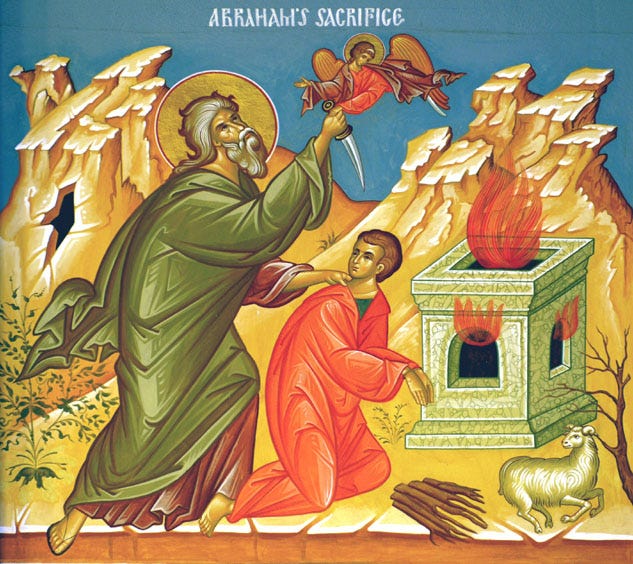

Sacrifice plays a central role in both narratives. Abraham’s willingness to offer Isaac prefigures the ultimate sacrifice of Christ, while the covenantal blood of Exodus 24 foreshadows the sacrificial nature of the New Covenant, sealed in the blood of Christ. St. John Chrysostom emphasizes that Abraham’s faith was not merely tested in his willingness to sacrifice Isaac, but in his unwavering trust that God’s promise would still be fulfilled even if Isaac were slain.[4] The dialogue between Abraham and Isaac illustrates the prefiguration of Christ’s sacrificial role. Saint John Chrysostom writes:

Mark too with what gentleness Isaac asks, “Behold the fire and the wood, but where is the lamb for a burnt offering?”: and what was the father's answer? “My son, God will provide Himself a lamb for a burnt offering.” (Genesis xxii. 7,8.) In this he uttered a prophecy that God would provide Himself a burnt offering in His Son, and it also came true at the time.[5]

This interpretation underscores the prefiguration of Christ's sacrificial role, with Isaac symbolizing the obedient son and the ram representing Christ as the Lamb of God.

Similarly, Moses’ mediation of the covenant on Horeb prefigures Christ as the true Mediator between God and humanity. In Exodus 24, the people are sprinkled with the blood of the covenant, a sign of divine election and consecration.[6] Here, too, the act of sacrifice transcends its immediate ritual function, prefiguring the Eucharistic mystery in which the New Covenant is established through the blood of Christ. The Orthodox liturgical tradition reflects the typological relationship of the covenantal events found in the Old Testament to Christ’s Passion. The Synaxarion of the Sunday before the Nativity of Christ states "Bound for slaughter, O Isaac, you are a figure of the Word Most High, who shall come to be slaughtered".[7] This liturgical reading reinforces the idea that Isaac’s binding is a direct prefiguration of Christ’s Passion as wee as Isaac’s silent submission as a model of ascetic obedience.

Conclusion

The covenantal narratives of Abraham and Moses are theological paradigms that points to the salvific work of Christ. Their typological connections reveal a deeper pattern of divine providence, in which sacrifice, obedience, and covenantal fidelity prefigure the Mystery of Redemption. In the divine economy of our merciful Lord, there is a recognizable pattern in how He continually strives to heal our fallen state and restore within us the image in which we were first fashioned. This merciful order reveals itself in the parallel wonders of Passover and Holy Pascha, the offering of Isaac and the sacrifice at Golgotha, the covenant at Sinai and the teaching of the Sermon on the Mount.[8]

Genesis 22 and Exodus 24 invite mankind into a deeper participation in the Mystery of Salvation, where the ultimate ascent is not merely toward a mountain, but toward the divine presence. In the end, both Abraham and Moses point to Christ—the true Sacrifice, the ultimate Mediator, and the fulfillment of God’s covenant with humanity.

-GP

[1] Luke 24:44

[2] Gregory Palamas, The Triads, ed. John Meyendorff, trans. Nicholas Gendle (New York: Paulist Press, 1983), 1.3.19.

[3] Ibid., 1.2.1.

[4] John Chrysostom, Homilies on Epistle to the Hebrews, Homily XXV, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, vol. 14, edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, Fourth printing, 2004), 478.

[5] John Chrysostom, Homilies on the First Epistle of St. Paul The Apostle to Timothy, Homily XIV, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, vol. 13, edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, Fourth printing, 2004), 458.

[6] John Chrysostom, Homilies on Epistle to the Hebrews, Homily XVI, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, vol. 14, edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, Fourth printing, 2004), 444.

[7] Eugen J. Pentiuc, The Old Testament in Eastern Orthodox Tradition, (Oxford University Press, 2014), 290.

[8] Ibid., 51.